NATO’s video game frontline, 09/10/2025

It’s all gone a bit John le Carré 🕵️

I find out what NATO is thinking about video games and the information war

Supercell CEO warns new EU rules could “kill one of Europe’s few tech success stories”

Battlefield 6 fights its way to the top of the weekly releases

Hello VGIM-ers,

Tomorrow is World Mental Health Day. Last year, I encouraged readers to take a moment in their day to ask how a colleague, friend, or family member is getting on. I’m doing the same this year.

The past 12 months have proven genuinely challenging for my own mental health.

My life, in many ways, has been great. I’ve travelled the world. I’ve met wonderful, life-changing people. I’ve pursued my dreams in a way I never thought I was capable of.

I’ve also worn myself down into a tired nub. Working on the book alongside my normal day job has burnt me out. My personal relationships have suffered, in ways I regret. I’ve struggled to stay on top of my physical health, too.

But through it all, I’ve stayed afloat. And a big reason for it is my mate Carl.

Through a tough year, Carl has messaged every couple of weeks with the message “How is George?” He sends it because, in his words, “you don’t strike me as a man who often gets to articulate everything.”

By asking, Carl allows me to. Whether I’m high, low, or hovering in between, his messages have given me space to breathe. In that space, I’ve been able to honestly express how I’m doing. That’s allowed me to gently turn the pressure valve in my head, providing comfort in the process.

So today, I once again ask you to channel your inner Carl. Pick up your phone. Ask one person in your contacts list how they are doing today. Listen to what they say.

You can’t solve their problems. That’s their job to do, and they, more than anyone, know it.

But taking on the world takes strength. And sometimes, your inner strength benefits from some friendly fortification,

So whether you favour pinging memes, sending texts, or, lord forbid, ringing someone, take a minute today to check in with somebody.

It might just make someone’s day, and their life, a little easier.

The big read - NATO’s video game frontline

Frozen up: In 1991, the Cold War finally froze over. After decades of brinkmanship, divvying up of countries, and a smidge of espionage, the Soviet Union fell. The capitalist West won. And we were never challenged again, living our lives peacefully forever. The end.

Thawing out: Well, that’s how Francis Fukuyama told it. The reality, though? It’s been a little different. Over the past two decades, the temperature across Europe has steadily risen again. Russia has embarked on a hybrid war against Ukraine that’s rippled across the continent. It has sent hundreds of thousands of its citizens to their deaths in a needless war. Its air force has been flying jets through the airspace of other Eastern European countries. It has relentlessly sown disinformation across the world, flooding digital channels with its narratives to baffle, unsettle, and exhaust people living in democracies across the world.

History lesson: So, what can be done about it? Well, the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) has some ideas. Founded in 1949, NATO is a political and military alliance of 32 states that are committed to supporting one another if they’re attacked by someone else. And while NATO definitely isn’t at war with Russia (trust me, you’d know), it does convene military, political, industry, and academic expertise to discuss how to defend itself against new forms of war that seep across traditional frontlines.

All Noisy on the Digital Front: One of NATO’s big areas of focus is fighting back against digital information warfare that seeks to undermine our democratic processes. And on Wednesday 8th October, NATO’s Strategic Communications (StratCom) Centre of Excellence convened bigwigs from across the world for the tenth time to talk about exactly how it can do that.

Digital frontlines: But in contrast to previous events, NATO’s conference had a different focus this year. Until now, experts have come together to discuss “emerging trends in social media.” This year, the conference explored the full breadth of “digital frontlines” the information war is being fought. And one of those frontlines, somewhat unfortunately, is video games.

Playing for power: So, how is information war being waged in video games? What’s the risk within the space? And how can we defend players from harm in a way that doesn’t bore them to tears? I hopped on a flight to Riga to find out.

War gaming

K-Propaganda: Strategic digital communication by militaries and political organisations has come a long way in the past decade. Over the course of my day at the conference, I was honestly surprised by how creatively these organisations are reaching digital audiences. The opening panel about the future of social media spoke pragmatically about the challenges of AI chatbots as a possible one-on-one channel for disinformation. Ben Tuft from NATO’s StratCom team discussed the organisation’s creator outreach programme and how it reached over 200m people without spending a dime. And Daphne Xu from Singapore’s Ministry of Defence discussed its creation of a synthetic K-pop band called Soda to act as influencers on its behalf. Welcome to a weird new world, everyone.

Getting in the game: But when it came to games, things were less sophisticated. The good news is that loads of people wanted to find out more about the medium. The room, which hosted the dramatically titled Entertainment or Exploitation panel, was packed, with political officials and uniformed military representatives filling it from front to back. But knowledge of games was low. Whereas the session about creators featured an in-depth look at effective campaigns in action today, the games session was much more introductory. Attendees know games are important to the conduct of information war. They’re just not sure how.

Panel: Two panellists quickly set about bridging the knowledge back. The first was Dr Joshua Foust, Associate Professor at Syracuse University. He presented his research exploring how video games and the communities around them have led to the creation of a contested information space where chatter and ideas flow back and forth. Wherever information spreads, influence follows. And according to Foust, military and political actors across the world naturally want to control it.

Assuming direct control: “When you have militaries in gaming, you’re dealing with an imperative for control,” Foust explained. “There’s a need or interest to try to control the spaces we’re in and to shape narratives.” Often, that leads to organisations making what Foust called “bizarre choices” that many of us in the industry are familiar with. Remember America’s Army, the video game created by the US military to encourage recruits into the armed forces? Turns out that, according to Foust, it wasn’t just an ineffective recruitment tool. It also caused reputational blowback against the military, leading to the US military rethinking its approach to using games to reach audiences.

Getting a tune out of games: But even though some of the interventions miss, Foust explained that there is still serious investment in campaigns within the gaming space by governments and the institutions that sit within them. “Agencies aren’t doing this for fun,” he said, when referring to work done within games within the US government more broadly. “They’re instrumentalising games to get something done.”

Censored: Outside of the States, which is where the majority of Foust’s research focuses, he identified two main ways this is happening. The first is censorship, where state-mandated rules or self-imposed censorship restrict what can be communicated within game spaces. On the state-ordered front, Foust demonstrated how Chinese-developed Marvel Rivals banned terms such as ‘Tibet” and “Taiwan” within the English language chat for the game. He cited this as an example of how games can act as a medium for “exporting censorship” to other countries. And on the self-censorship side, Foust highlighted Blizzard’s crackdown on the Hearthstone streamer Blitzchung for sharing pro-democracy messages during a live-streamed tournament in 2019. Blizzard claimed the sanction was for breaching tournament rules. US politicians argued otherwise.

Bomb the Squad: Second, Foust spoke about how games and game influencers are being used to actively promote narratives. Squad 22: ZOV, a remarkably shit tactical shooter (note: I have played it), is still live in plenty of Steam stores across the world, despite the content of its Ukraine War-focused game being supported (and almost certainly funded) by the Russian Ministry of Defence. The Wagner Military Group, meanwhile, has used a tame video game streamer called Grisha Putin to promote its narratives abroad. As well as livestreaming war games from its offices in St Petersburg, he’s also popped up in Burkina Faso promoting a banned mod of Hearts of Iron IV - one that implies Russia is the only true partner of a free Africa.

Less than super spreaders: And while neither Squad 22: ZOV nor Grisha Putin has reached a huge audience directly, Foust argues that, well, it kinda doesn’t matter. Its aim isn’t solely to get people playing the game; it’s to feed the ‘extra-ludic’ communities of young men who sit within games culture at large to encourage them to organically promote the party line. “Russia has been very good at presenting a pro-Russian perspective as transgressing the official US position,” he said, highlighting both its political messaging and social messaging on issues such as LGBTQ+ rights. “So, it then became a good one for gamers who want to be transgressive.”

Media multipliers: This encourages these audiences to transgressively post about these games or streamers to their communities, multiplying the message. It also encourages mainstream Western media to cover the story, leaning into their lack of video game literacy to uncritically promote the effectiveness of these measures to millions of people. This is called ‘perception hacking’, something that leads to an over-estimation of Russian strength (and an under-estimation of what we can do about it).

Jam-tastic

Serious games: One-nil to the autocrats then? Well, sort of. Foust says that autocracies have a major advantage because they “take games seriously”, funding and supporting information campaigns within the medium in a way democracies generally aren’t. If they’re ahead of us, he says, it’s largely because they want it more than we do.

Jamming all over the world: But there is hope that democracies can push back. Maria Burns Ortiz is the Executive Director of Global Game Jam, the funsters behind the annual game design competition beloved by most of the industry. Her team secured funding from the State Department’s now dearly departed Global Engagement Center to fund a game jam against disinformation. And they discovered that game developers and communities are very happy to participate in democracy saving interventions, provided it isn’t boring, unimaginative, or seen as ‘propagandist’.

Chocolate-covered broccoli: “We surveyed game developers to find out whether they believed that games could counter disinformation,” Burns said. “We found that about 80% did. But when we asked developers if they wanted to make games about disinformation, that dropped to about 50%.” After diving into the details, it turned out that asking developers whether they wanted to make “educational” games about “disinformation” actively discouraged them from getting involved. Being dull, once again, proved to be anathema to engaging audiences on political topics.

All over the world: To respect its research findings and appeal to an audience of game developers based in 26 countries across the world, the Jam’s organisers made a few clever decisions. The game jam was named Ctrl+Alt+Disinfo to soften the term ‘disinformation’. The event’s tagline encouraged people to “create games to make people think critically”, rather than encourage companies to create dreaded edutainment. And developers were taught about the mechanics of disinformation through resources and other games like Harmony Square, allowing developers to think about the fun that could be found in the juicy mechanical and systemic challenges that disinformation presents.

999, just out: The Jam’s positioning proved to be effective. By early 2025, 172 games had been made that taught players about disinformation by getting them to play around with the mechanics that underpin it. Overall, this led to 999 people grabbing their game engines and participating in the game jam. And unsurprisingly, the Jam’s theme proved remarkably popular in Ukraine - leading to a massive spike in participation.

Counter-attack: Since the Jam ended, Burns said that several games made for it have either made it to release or are on the pathway to publishing. But she also suggested that the most significant benefit of the jam is that it has taught hundreds of game developers about how to tackle the threat of disinformation within games. “They [developers who participated] say to me that one of the things they’ve carried forward is how to counter disinformation,” explains Burns. And with the games industry being a relatively tight-knit community, that means it is more likely that knowledge will spread to the rest of the sector - innoculating the industry against some of the risks of information warfare in the process.

Collective action

DOGE’d and out in Riga: Problem solved then? Well, not really. The Global Game Jam’s work on disinformation was going really well. Then, the US government got DOGE’d by Elon Musk’s army of weeby little men. A third phase of funding that would have supported efforts to celebrate the Jam’s work across the world was pulled from the organisation as part of wider US government cutbacks. This dampened the effectiveness of the Jam’s work, adding a rueful ‘what if’ to a global success story.

Talking tactics: But outside of these tactical problems, democracies face two bigger issues in the contested information space that we like to call games. The first is the breadth of issues emanating from the industry. Andrea Liebman, Senior Analyst at the VGIM-approved Swedish Psychological Defence Agency, ran a poll on the ‘main concern’ amongst attendees about malign actors in games. Radicalisation, the distribution of propaganda through games-related social media, and manipulation of game design a la Squad 22: ZOV topped a list of six hand-picked concerns from people. But in October 2023, the University of Lund identified 40 tactics that malign actors use to influence games. One 45-minute-long panel could never hope to address all those issues, however much ground it covered.

Funding crunch: Second, and interrelated, there isn’t enough support for organisations and individuals who are concerned about these issues to meet these challenges. Only a handful of researchers like Foust are exploring the issue, which means it is hard to identify the biggest problems and how to solve them. Organisations like the Global Game Jam are doing good work, but they live hand to mouth in a way that prevents long-term strategic interventions. Military and political officials clearly have an interest in addressing challenges in space, but it is clear that their thinking around games is still early stage. Industry, meanwhile, was alarmingly conspicuous in its absence. This means it could be hard to find enough support, whether financial or otherwise, to make meaningful interventions in the space in the way that autocracies are gleefully doing so.

On the up: However, let’s end on the positives. NATO’s decision to run a constructive session on the challenges within video games is heartening. The level of interest in the room in the topic, and the seriousness with which people engaged with the issues raised, shows that the cultural conversation around games has shifted in a meaningfully positive direction. And there seemed to be genuine support for more research, more investment, and more help for players to stop them from being subjected to information campaigns, even if it wasn’t entirely clear how that could happen.

Call to (in)action: So yes, video games and the communities around them now form one of the digital frontlines on which information war is waged. But if the games industry can stop hiding under the covers, embrace our true role in society, and head out into the world just a little bit, we can do our bit in protecting democracy from the march of authoritarianism that, really, at its heart, runs counter to the fun, joy, and freedom we want our players to have.

News in brief

Clash of Bans: Illka Paananen, CEO of Supercell, has written a letter criticising the EU’s Consumer Protection Cooperation Network’s in-game spending proposals. Paananen warns that the proposals, which caused serious consternation amongst the industry upon publication earlier this year, risk killing “one of Europe’s few tech success stories”. He goes on to encourage the CPC and Commission to engage with the industry, lest “good intentions destroy competitive advantage.” Yikes.

Public Discord: Discord has revealed that a “small number of Government ID images” shared with a third-party age-verification provider have been accessed by an “unauthorised” party. As well as accessing images of documents like driver’s licenses, the hackers also gained access to people’s Discord usernames, payment information, and their IP addresses. Three cheers for the Online Safety Act!

Pot of Gold: Ireland’s game development scene is celebrating following improvements to the country’s Digital Games Tax Credit. The credit has been amended to allow developers to claim for post-development work, addressing a major failing with the original policy. It has also been extended until 2031, allowing developers to pile in to claim the cash.

Game Passing on the costs: Xbox has doubled the price of Game Pass to a hard-to-ignore $30 a month. California Governor Gavin Newsom blamed the cost increase on Trump’s tariffs. Bloomberg Cecilia D’Anastasio revealed that the increase was caused by a whopping drop in day-one revenue for the Call of Duty franchise, which saw Microsoft miss out on hundreds of millions of dollars.

Nintendon’t get your facts wrong: Japanese politician Satoshi Asano has been forced to apologise after claiming Nintendo had lobbied the national government to encourage it to resist generative AI. The usually quiet Mario maker issued a statement denying Asano’s claims, leading to a grovelling apology. It did, however, say that it’d continue to “take necessary actions against infringement of our intellectual property rights.”

Moving on

After a decade at Riot Games, Dan Sutton has been named Head of Games Marketing at Netflix… Oliver Bulloss is replacing Schraga Mor as CEO for MTG… and Andrew Watson is moving from COO to CEO at Hutch…Elinor Meijer has been promoted to Communications Specialist at Sharkmob…And Summer Tang is now the Operations Director at YRS TRULY…

Jobs ahoy

Don’t immediately start fighting with one another for this job, but CD Projekt Red is hiring a Public Policy Expert… SEGA is on the lookout for a new Head of Brand Marketing… Epic Games is recruiting a Creator Programs Director and a Marketing Director, UK and Nordics… Behaviour Interactive is seeking a Creative Director… and Roblox is on the hunt for a Head of Investor Relations…

Events and conferences

Game Republic New Horizons, Middlesbrough - 16th October

Twitchcon, San Diego - 17th-19th October

Games Industry Conference, Poznan - 23rd-26th October

Paris Games Week, Paris - 30th October-2nd November

AI and Games Conference, London - 3rd-4th November

Games of the week

Battlefield 6 - Latest entry in EA’s ever-popular multiplayer first-person shooter series rolls out on Steam, Xbox, and PlayStation.

Little Nightmares 3 - Nothing screams scary than problem-solving with your friends in the newest game in Bandai Namco’s horror series.

Bye Sweet Carole - Continue your preparations for spooky season with another whimsical indie horror inspired by Alice in Wonderland.

Before you go…

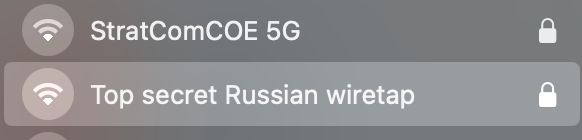

What’s the funniest thing you can do with the name of your personal wi-fi network at a conference hosted by NATO?

The answer, it seems, is this.

Do svidaniya, VGIM-ers.

Keep up with VGIM: | Linkedin | Bluesky | Email | Power Play |